2.14.20 Crispus

As we arrive smack-dab in the middle of Black History Month, let’s state one truth very plainly:

One of the first persons to die in the American war for independence was a black man.

Folks have argued over exactly who he was.The only two surviving documents that refer to him describe him as “mulatto,” “Indian,” “a tall man,” and “stout.” Some historians point to a notice in the local paper that stated, “Ran away from his Master William Brown of Framingham on the 30th of Sept. last a mulatto Fellow, about 27 years of age, named Crispus, 6 Feet and 2 inches high, short curl’d Hair, his Knees near together than common,” as evidence that he was perhaps a former slave. And his last name was common among the Wampanoag Indians, and may have come from their word, “ahtug,” meaning “little deer.” From all the evidence, the most likely scenario is that his father was a black slave and his mother a native, and historians refer to him as Crispus Attucks.

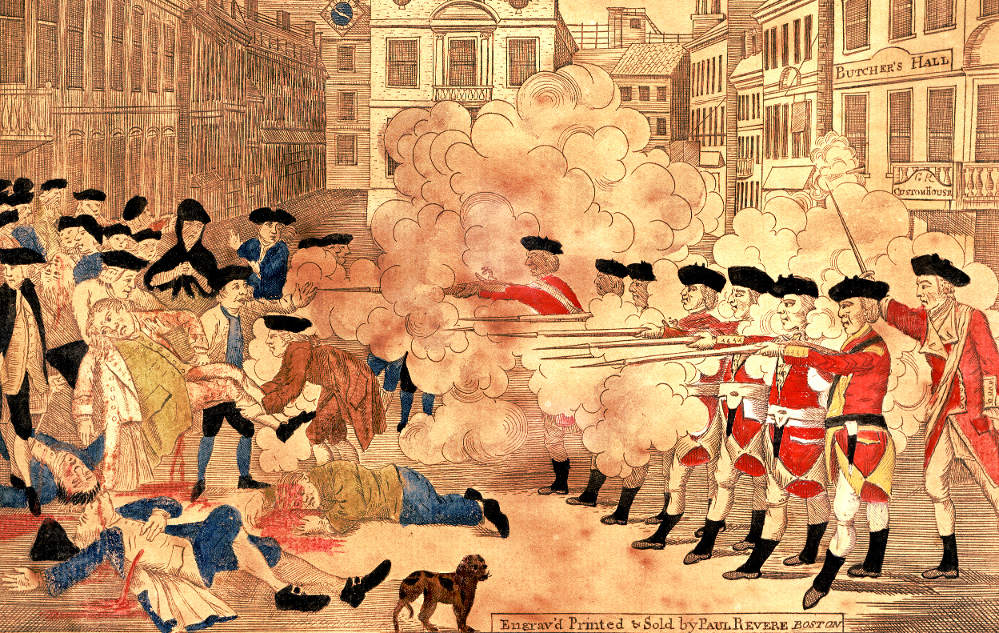

The larger, more important argument is over his participation in the events of March 5, 1770. On that day, a group of men, probably rope-makers, were taunting an English soldier who was stationed on guard at the Customs House. The soldier, Hugh White, struck one of the men named Edward Garrick in the ear with the butt of his musket, and the men temporarily dispersed. But they soon returned in greater numbers, and someone rang the meeting house bell, which caused a crowd of about 400 to arrive with buckets of water thinking a fire alarm had been sounded. In response, the English officer in charge, Captain Thomas Preston, forced his way through the crowd with a squad of seven more soldiers, with much pushing and shoving. Some of the colonists, perhaps led by Crispus Attucks, struck the soldiers with sticks and pelted them with snowballs, and dared them to fire.

Open fire they did. Four Americans were killed instantly: Samuel Gray, Samuel Maverick, James Caldwell, and Crispus Attucks.

The citizens of Boston dubbed the event, “The Boston Massacre,” and treated the victims as martyrs for liberty. Eyewitnesses to the event claimed Attucks and others had only taunted the guard, and most had been minding their own business when the English opened fire. But when the soldiers went on trial, they were defended by John Adams, who put the blame on the colonists. He called them “a motley rabble of saucy boys, negroes and molattoes, Irish teagues and outlandish jack tars.” As for Attucks, Adams accused him of being the leader of “the dreadful carnage,” who had “hardiness enough to fall in upon them, and with one hand took hold of a bayonet, and with the other knocked the man down.” In the end, the soldiers were acquitted.

The people of Boston were enraged. They laid the victims in state in Faneuil Hall for three days and then buried them in Granary Burying Ground – which would later contain notables like John Hancock – despite laws prohibiting the burying of blacks there. For the next several years, the citizens of Boston recognized the anniversary of the Massacre with increasing revolutionary fervor, and summoned the “discontented ghosts of the victims.”

In later years following the Revolution, the argument over Attucks continued. In 1858, black abolitionists called for a “Crispus Attucks Day,” which angered southerners and contributed to the outbreak of the Civil War. In 1888, a Crispus Attucks Monument was erected in Boston Common, against the wishes of the Massachusetts Historical Society, who considered him a villain.

To this day, historians are divided on what to make of him. Was he, as John Adams described him, “mad,” and “whose very looks was enough to terrify any person”? Or should he be remembered as described by poet John Boyle O’Reilly, “the first to defy, the first to die.”

He remains a mystery. But these truths are certain.

His name was Crispus Attucks.

He was a black man.

And he will be forever remembered as “The first martyr of the American Revolution.”