Week 15: Taxation Nation

You’re probably pretty grumpy right about now. And I’m here to explain why.

The Founding Fathers were apprehensive from the beginning. They had just broken away from an Empire that they thought had taxed them unfairly, to pay for the cost of the French and Indian War. The Founders were also distrustful of one another, concerned that some states would figure out a way to get an unfair advantage over the other states. So they acted very conservatively and purposefully made taxation really difficult. They included a clause in the Constitution that stipulates that if the federal government wants to collect a “direct” tax – that is, a tax on “stuff” like people or property – it would have to be approved by and apportioned equally across all of the states. For example, if a state contains 10% of the people in the country, a national tax on headcount would require that state to collect and send in 10% of the requested revenue. That process would be hard to approve, hard to calculate, and hard to collect, making the prospect of levying “direct taxes” very complicated.

But what about a tax on income? Income doesn’t come directly from existing “stuff” but indirectly from dynamic activity like hours worked or goods sold. Unlike “direct” taxes on stuff, “indirect” taxes were less scary to the Founding Fathers, because people have a choice in the matter, they can alter what kind of work they do, and what sort of transactions they make (as opposed to altering who they are). So, from the beginning, the Constitution has never really restricted Congress from collecting “indirect” income taxes if they wanted to.

It didn’t happen for a very long time, and, not surprisingly, it was a war that triggered it. In 1861, the Civil War got so out of control, and proved to be so expensive, that something had to be done to pay for it. That year, the government passed a Revenue Act that mandated a flat tax of 3% on all incomes above $800. The second year of the war got quite a bit nastier, and more expensive, and so in 1862, the program was revised to be a graduated tax of between 3% to 6% for all incomes over $600. And this tax proved to be very imbalanced indeed, as the lucrative, labor-intensive industrial states of New York, Pennsylvania and Massachusetts bore the brunt of the cost.

These wartime taxes were supposed to expire in 1866. But the war had cost a bundle, and the taxes dragged on into 1872. By then folks started getting used to paying income taxes, and it was only a matter of time before the government became addicted to easy money. In 1894, Congress enacted a permanent national income tax for the first time.

“Now hold on there!” said the Supreme Court just a year later. (It was another one of those complications that the brilliant Framers invented to muck up the works and make things hard to accomplish.) The Court ruled by a 5-4 margin that many kinds of income – like rent collected on land, or dividends derived from stocks – weren’t really transactions, they were value inherently generated by “stuff”. So those things should also be considered “stuff” and couldn’t be indirectly taxed as income. By this ruling, the Supreme Court severely limited Congressional ability to tax incomes. Case closed.

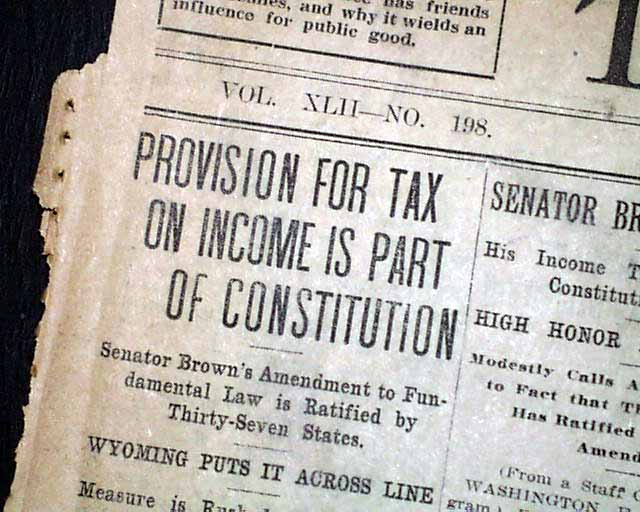

“Oh yeah? Watch this!” Congress responded. (Oh, those checks and balances!) In 1909, they drafted the 16th Amendment, which overrode the Supreme Court’s decision and gave Congress the power to “collect taxes on incomes, from whatever source derived.” Two-thirds of the House and the Senate approved it, and three-quarters of the states ratified it. (Only Utah, Virginia, Connecticut and Rhode Island rejected it; Pennsylvania and Florida deferred.) And with its ratification in 1913, Congress granted itself the permanent, unlimited power to tax every source of income of every individual (as well as every corporation, because, like, as Mitt Romney says, companies are people too).

The beast was unleashed. At the time of the Amendment’s passing, the highest tax rate on income was 13%. But just five years later, in the wake of another expensive war, Congress raised the highest tax bracket by just, well, um…just a little bit…just a smidge…to, um…77%!

Yikes. Since that time, income taxes have proven to be the great “get out of financial jail” card for Congress. The highest rates fell for a few years, until the Great Depression hit, and then spiked again into the 60% range. For most of the 20th century, the graduated rates ranged wildly from about 15% for the lowest tax brackets, to as high as the 80s and 90s for the highest brackets. In the 1990’s, rates for the highest brackets were lowered back down into the 40’s (so that rich folks can Supply-Side-trickle money down to the rest of us, thanks!), and they have remained there ever since.

And so, welcome to Tax Day 2023, and the 110th Anniversary of the 16th Amendment. We’ve been paying income tax consistently for over a century. And in the wake of Afghanistan, the longest war in our history – and lots of other expensive things – the country is approximately $32 Trillion in debt. It’s gotta get paid.

Thankfully, you live in a country where you can raise your voice and do something about it. In theory at least.

But in the meantime, make sure your check’s in the mail by Tuesday.