Week 2: Four Soldiers

Here’s the how some things get remembered, and some do not.

Robert E. Lee was born on the 19th of January in 1807. At the end of the Civil War, when he surrendered to Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House in Virginia, he probably feared that he might spend the rest of his life in jail, or worse. But Grant was generous, and declared that soldiers of the Confederacy would be “allowed to return to their homes, not to be disturbed by United States authority so long as they observe their paroles and the laws in force where they may reside.” Nobody was going to be tried for treason; horses could be kept for plowing fields in the coming spring; and officers were allowed to keep their guns (for purposes both lawful and nefarious).

Lee became President of Washington College (later renamed Washington and Lee) and lived there peacefully for five years until his death in 1870.

There is a second Confederate general that you have probably heard about named Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson. He was also born in January, on the 21st, in 1824. He orchestrated some incredible victories in his native Shenandoah Valley, and was instrumental in the greatest long-odds southern victory of the war, at Chancellorsville in the spring of 1863.

Unfortunately for Stonewall, his greatest victory would be his final one, as he was killed by friendly fire at the end of that battle, and he wouldn’t participate at Gettysburg just two month later.

Which brings us to a third southern general whose name may not sound so familiar. He was Lee’s most senior and longest-serving subordinate at places like Seven Days, Fredericksburg, Antietam and Gettysburg. After which he shipped west and won a huge and unexpected victory at Chickamauga. And then he came back east and was the south’s best fighter right up to the end. Lee called him, “My old war horse.”

All of which means he was without question the second-most important southern general after Lee. His name was…James Longstreet. And incredibly, he was also born in January, on the 8th, in 1821. And he lived a good long life, making it all the way to 1904.

So why has southern culture largely forgotten him? The answer is two-fold. First, at Gettysburg, he implored Lee not to send George Pickett’s division to charge into the Union center, correctly predicting that it would end in a southern bloodbath. But even worse, after the war, he committed the ultimate sin of accepting defeat and supporting Reconstruction, Emancipation, and Black Suffrage.

He would never be forgiven. In the late 1800’s, when statues and memorials to the Lost Cause started to spring up all over the place, Longstreet was nowhere to be seen. You could find a statue of Lee riding his horse Traveler in town squares all over the south. But if you paid a visit to Stone Mountain in Georgia, to gawk at the largest bas-relief sculpture in the world, you would see what looks like three soldiers on horseback: it’s Robert E. Lee, Stonewall Jackson, and…um…President Jefferson Davis.

The shunning of Longstreet became official in 1889, when the state of Virginia created Lee Day, and in 1904, when it morphed into Lee-Jackson day. Four other southern states adopted that holiday.

Meanwhile, in a parallel universe, starting around 1873, New York declared a new state holiday, Lincoln Day, to be celebrated on his birthday, February 12. It was adopted by ten other states, including – surprisingly – Texas.

All of which led to a brutal century-long struggle in the United States which could be called the Battle of Regional Holidays. The northern states pushed to fold Lincoln’s state holiday into a national recognition of George Washington (who was born on either February 11 or 22; that’s another story), but the southern states consistently refused. And as it turned out, in this second Civil War, the South had the eventual victory. In 1968, when Congress passed the Uniform Monday Holiday Act, Washington’s Birthday was designated for the third month in February. But though we all commonly call it President’s Day, officially Abraham Lincoln has nothing to do with it.

And in Virginia, Lee-Jackson Day lived on.

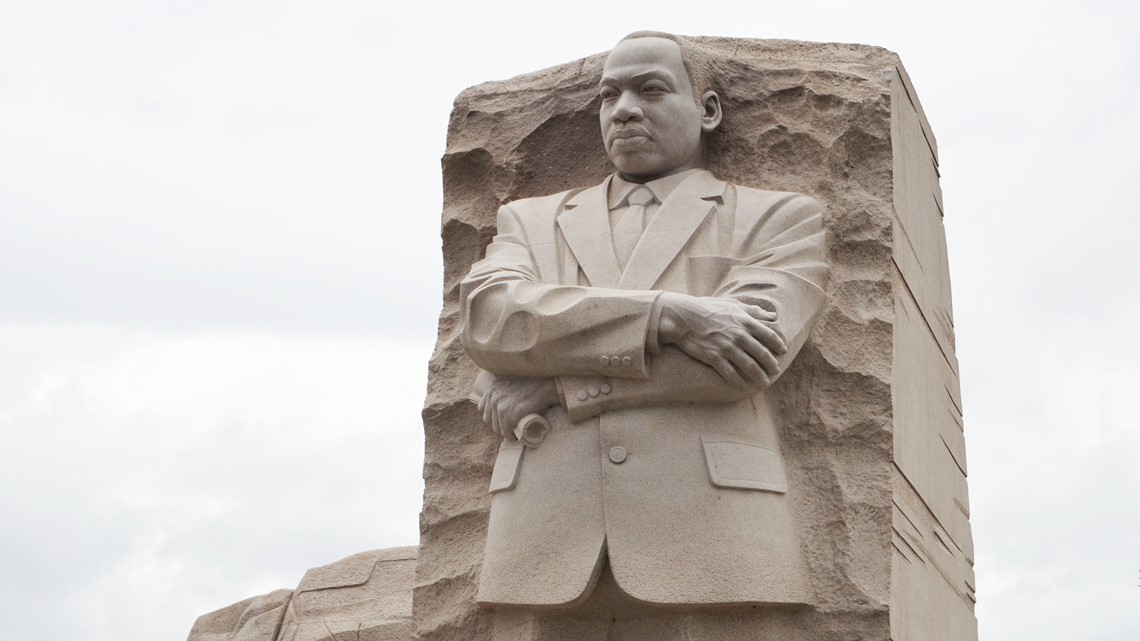

But then along came a fourth guy, a non-violent soldier, who was also born in January, on the 15th, in 1929. Interestingly, he was from Atlanta, a mere 20 miles west of Stone Mountain. And he would go on to become one of the most important Americans in history. From the Montgomery Bus Boycott in 1955 to the I Have A Dream Speech in 1963, the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, he would do more to fulfill the promise of the Civil War – equal rights of all citizens – than any other person.

For this, Martin Luther King, Jr. would be assassinated, aged 39, in 1968.

Which, some time later, would quite poetically lead to this: in 1983, President Reagan signed into law a new federal holiday honoring MLK, to be celebrated on the third Monday in January. And in one of those weird cosmic coincidences that makes you believe in a higher power, the first national MLK Day landed on January 20, smack-dab right in between Lee’s birthday and Stonewall’s.

Virginia was not amused. In response, a year later, they created the most grotesque monster of a holiday imaginable by declaring the day Lee-Jackson-King Day, which kinda references January 15, 19 and 21, and definitely combines two Confederate war heroes with a descendant of slaves.

Then, in 2000, the chimera got sliced in half, with MLK Day remaining on the third Monday in January, and Lee-Jackson Day moved to the preceding Friday to cynically bracket the weekend. It was a tortured compromise, and over the next decade, recognition of Lee-Jackson day began to dwindle in the DC suburbs, the capital of Richmond, and progressive college towns like Charlottesville and Blacksburg.

It all came down to April of 2020, when Virginia finally eliminated Lee-Jackson Day entirely, and replaced it with a new state holiday to be observed on the Tuesday after the first Monday in November. Every resident of the state gets the day off so they can go vote. It’s called Election Day.

The Civil War ended when Virginia surrendered in April of 1865. It only took 155 more Aprils for the conflict to finally be resolved. Universal convenient suffrage had come to the Old Dominion.

(And as for James Longstreet, there are exactly two statues of him in America; one of him standing, near his former home; and the other astride his horse, life-size, dark bronze, not on a pedestal, hiding in the trees, near Pickett’s Charge, at Gettysburg.)