Week 40: Holiday #8

Welcome to the most conflicted holiday on the calendar.

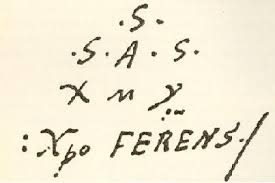

The trouble starts with the very name of the thing, to wit, there never was an explorer named Christopher Columbus. He may have been called Christoffa Corombo in his native Genoa, or Cristóvão Colombo in Portugal, or Cristóbal Colón by the Spanish. He signed documents using a mysterious monogram, the initials “S SAS SMY” and a signature that reads “XPoFerens.” It may be Greek/Byzantine/Latin shorthand for “Christopher.” But others have translated it as “Ferryman of Christ.” If so, he may have invented it as a “stage name” to endorse his accomplishments. In which case, his real name may be unknown.

Historians would have us believe he was an illiterate weaver’s son who stowed aboard Italian trade ships, learned navigation and cartography, taught himself 3 languages, sailed west as far as Iceland, was shipwrecked in the Atlantic, swam 5 miles to the Portuguese coast, married into nobility, was rejected by the heads of Portugal, Venice, and England, before pestering Queen Isabella for seven years until she finally hired him. Sounds plausible.

He was controversial even in his own time. After his first voyage, he was knighted. After his third voyage, he was arrested and brought home in chains. He fought legal battles for the rest of his life to protect his earnings and secure his legacy. He died and was buried in Valladolid. Then the body was moved to Seville. Then perhaps to Hispaniola. Then maybe to Havana. Perhaps back to Seville. In 1892, Seville gave some of his bones to Genoa. There are tombs in all of these places.

To some, he is a symbol of salvation and civilization. Spain celebrates his day as “Fiesta Nacional.” Italian-Americans claim him as their own with huge parades in many cities. And in South America, “Dia de la Raza,” has traditionally celebrated the melding of Spanish, African and Indian races.

But to others, he has increasingly come to represent persecution, exploitation and genocide. Back in 1990, 350 representatives from various indigenous peoples met in Quito, Ecuador to mobilize against the quincentennial commemoration of Columbus Day. They were supported in 1992 by the United States Council of Churches, which declared, “What represented newness of freedom, hope, and opportunity for some was the occasion for oppression, degradation and genocide for others.”

From that point on, the reworking of Columbus Day has been simmering across the hemisphere. In 2002 in Venezuela, Hugo Chavez renamed the holiday Dia de la Resistencia Indigena. Two years later, on October 12, 2004, Columbus’ statue in the central square of Caracas was torn down and abusive graffiti sprayed on its pedestal. Other statues in other places followed soon after.

Today in Argentina, the day is known as Dia del Respeto a la Diversidad Cultural. Other South American countries just go with Dia de las Americas. And for many Latin Americans who have emigrated from their home countries, Dia de la Raza has been transformed, and now serves as a moment to advocate for their rights in a world ruled mostly by white northern Europeans.

The sentiment is much more widespread – and much closer to home – than you might think. In Hawaii, they have displaced Columbus’ discovery of America with a celebration of Polynesian discovery of those islands, and renamed it Discoverer’s Day. In South Dakota, the day is now known as Native American Day. Nevada and Iowa go with basic Columbus Day proclamations but have no holidays. In Alaska, they ignore Columbus altogether, no notice, no proclamation, no holiday, no worries. And if you live in Wisconsin, Minnesota, South Dakota, Illinois, Colorado, Washington or California, you can forget Columbus altogether and celebrate Leif Ericson Day on October 9.

In the end, there’s only really one thing that remains certain: the guy definitely landed in the Bahamas on October 12, 1492.

Definitely, no doubt about it. At least, if you’re using the Julian calendar…

…but since most of Europe adopted the Gregorian calendar in 1582 and jumped forward nine days…

…and then Britain and her American colonies did the same in 1752 and skipped two more…

…the truly equivalent date of his discovery of America is October 21, 1492…

…which means when the United States passed the Uniform Monday Holiday Act in 1968, they should have made Columbus Day the third Monday in October, instead of the second…

…never mind.

Enjoy your 2023 federal holiday #8.